Weird wanderings 1 – Candlemas fogou to fogou foray 2022

We stand at the centre of the ancient parish of Constantine, named after a long forgotten saint. Some say he could be the Roman emperor Constantine who first adopted Christianity as an official roman religion, though it was more generally thought that he was an evil and despotic west country Celtic king who mended his wicked ways and turned to a life of peace and piety, hence his symbol being a sword and a cross. In the C6 Gildas refers to him as “That tyrannical whelp of the impure lioness of Damnonia, Constantine.” He turns up again in the C11 Welsh life of St David and the C12 Cornish life of St Petroc and also as a medeaval saint in Scotland. Though as with all the old Celtic saint stories, their dramatis personae are just as much of this world as they are of the world of myth and folklore… but one cannot help but feel that whoever he was he has now become a kind of embodiment of the numinous spirit that broods over this local landscape.

The church is built on a vast oval raised mound, which in all probability there remains a prehistoric earthwork. The present church dates predominantly from the early C15 but before this stood a Norman church of which some of the stones still remain within the fabric of the walls; Before that in all probability, going from its Celtic dedication, a Celtic Christian monastery … and before that the earthwork could date from anytime between the Iron Age and the Neolithic age. In centre of the adjacent vicarage is an area walled off on all sides by solid granite walls with no entrance. Local tales say that it was built around a great stone standing stone, probably from the age of the earthwork or before, now hidden from common view.

We stand at the centre of the ancient parish of Constantine, named after a long forgotten saint. Some say he could be the Roman emperor Constantine who first adopted Christianity as an official roman religion, though it was more generally thought that he was an evil and despotic west country Celtic king who mended his wicked ways and turned to a life of peace and piety, hence his symbol being a sword and a cross. In the C6 Gildas refers to him as “That tyrannical whelp of the impure lioness of Damnonia, Constantine.” He turns up again in the C11 Welsh life of St David and the C12 Cornish life of St Petroc and also as a medeaval saint in Scotland. Though as with all the old Celtic saint stories, their dramatis personae are just as much of this world as they are of the world of myth and folklore… but one cannot help but feel that whoever he was he has now become a kind of embodiment of the numinous spirit that broods over this local landscape.

The church is built on a vast oval raised mound, which in all probability there remains a prehistoric earthwork. The present church dates predominantly from the early C15 but before this stood a Norman church of which some of the stones still remain within the fabric of the walls; Before that in all probability, going from its Celtic dedication, a Celtic Christian monastery … and before that the earthwork could date from anytime between the Iron Age and the Neolithic age. In centre of the adjacent vicarage is an area walled off on all sides by solid granite walls with no entrance. Local tales say that it was built around a great stone standing stone, probably from the age of the earthwork or before, now hidden from common view.

Below the church lays the Glebe gardens. This has been the property of the church for over a thousand years and was mentioned in the doomsday book as “Langostentyn”. The prefix “Lan” denotes an ancient Celtic Christian monastic enclosure. The old Celtic Christians came here one by one long before the Church of Rome ever came to our shores, in a way more akin to Hindu sadhus or wandering Sufi dervishes than anything we are familiar with as Christianity! This pushes the date back to possibly as far as the C4.

The Glebe garden is a strange little oasis of calm, nestled in a hidden combe at the foot of the fields below the Church. One enters by means of the old church path that leads to Bridge. Through a small gate one finds oneself in a tangled secret garden of paths, tiny lawns, a stream flowing amidst granite slabs and tangled vegetation. Once upon a time in the mid C19 it was the mill pool with leats feeding down to the old mine workings of wheel Caroline which once stood in the valley below. In the mid C20 it was an orchard but in the 1990s onwards it has been intermittently maintained as a community garden. Its terracing, unusual flora and remnants of stonework hint that this was once upon a time some kind of landscaped formal garden. Curiously however no records of this exist, and even more curiously, in the absence of any nearby big houses, it is hard to imagine who could have constructed and maintained such a garden. On entering the glebe one is greeted with a huge redwood sweeping heavenwards. In the early spring around the old festival of Candlemas at the beginning of February, it becomes a haven of snowdrops breaking through the cold earth heralding the early dawn of spring.

The Glebe garden is a strange little oasis of calm, nestled in a hidden combe at the foot of the fields below the Church. One enters by means of the old church path that leads to Bridge. Through a small gate one finds oneself in a tangled secret garden of paths, tiny lawns, a stream flowing amidst granite slabs and tangled vegetation. Once upon a time in the mid C19 it was the mill pool with leats feeding down to the old mine workings of wheel Caroline which once stood in the valley below. In the mid C20 it was an orchard but in the 1990s onwards it has been intermittently maintained as a community garden. Its terracing, unusual flora and remnants of stonework hint that this was once upon a time some kind of landscaped formal garden. Curiously however no records of this exist, and even more curiously, in the absence of any nearby big houses, it is hard to imagine who could have constructed and maintained such a garden. On entering the glebe one is greeted with a huge redwood sweeping heavenwards. In the early spring around the old festival of Candlemas at the beginning of February, it becomes a haven of snowdrops breaking through the cold earth heralding the early dawn of spring.

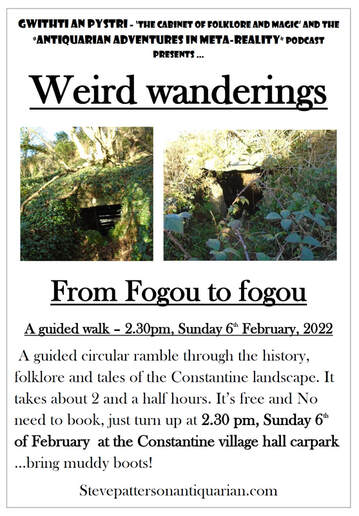

Its greatest treasure however lays at the back of the garden set back from the path in a small copse of hazels backing on the field beneath the church. A short tunnel disappears in to the slope. For many years you could enter its shadows, but now it has a steel grate fitted over its entrance to protect the bats roosting within. It goes in to the hillside about 10 feet before opening out in to small chamber. The tunnel is built in classic Fogou style with drystone granite sidewalls and massive granite lintels laying crossways to form the roof. The end chamber terminates in a massive granite slab which presumably is part of a cave like aperture in the granite bedrock. The side of the chamber, which also is composed of massive slabs, has several curious niches cut in to the wall at irregular intervals. Some local tales say that it is either a smugglers tunnel or an adit for the nearby Wheel Caroline, but it makes no sense to have an adit above the level of the mine and judging by the enormity of the slabs at the rear of the cave it is unlikely that this tunnel went anywhere apart from its present termination. It seems to me that it is built in the same manner as a Fogou, in an area where there are Fogous … so everything seems to point towards it being a fogou or a very old folly re-creating a fogou. I once informed the then Cornwall archaeological unit about the feature, and they politely but firmly informed me that it did not exist. I managed to get Paul Bonnington, the then archaeological warden for the national trust to look at it. He agreed that it was indeed a significant place, but without excavation it was impossible to say exactly what it was. Some of the orthostats around the entrance appear to have been cut with drill and wedges, which is a method used throughout the early modern period up in to the C20, but the rear section could possibly be a natural cave in the Granite. It remains an enigma and like all other fogous, there is a hint of the ‘otherworld’ that hangs like the mist in its shadows.

In the Celtic realms of the Scots and the Irish, Candlemas of the roman church, in which the candles were blessed (Another relic of a bygone age the church seems to have reluctantly adopted) was celebrated as the day sacred to St Brigit, the Mary of the Gael, to some it was known as “Imbolk”. It was also a time when the sacred wells, where the living waters flowed from the depths of the dark earth, were venerated. Here in Cornwall there doesn’t seem to be any specific observance of the wells on this day, Easter if anything was seen to be more fitting for this purpose. …but here at the dawn of the year when the stirrings of life seem so few and precious, it seems as good a time as any to pay ones respects. It is however the feast day of the old Celtic saint Uny. Uny was once venerated from central Cornwall down in to the far west, now only her name remains. On the edge of the Parish hidden in a wooded valley below a steep bank above the stream lays the old holy well of Uny, against the rising tides of inertia, mud and forgetfulness her living waters still flow.

Down a narrow gap between two houses down comfort lane on the edge of the village lays Comfort well. For many folks, when one thinks of a well, one thinks of a deep hole in the ground in to which one lowers ones bucket on a rope. There are some wells like this in Cornwall, but many of the wells are enclosed surface springs such as this one. The blurring of the line between what lays above and below the ground seems to be something inherent in both the Cornish landscape and the Cornish psyche. There is no evidence that this well was specifically recognised as a holy well with any kind of dedication attached but it was once one of the sources of domestic water for the village. The water courses beneath the land and the ways in which they flow are still an unseen mystery to the worlds of science and engineering; their mysteries are known only to the dowsers and the spirits of the wells. Many of the mine workings disrupted the unseen flow of the subterranean water courses and consequently many of the old springs and wells ceased to flow, but this well still runs pure and clear to this day.

At the end of comfort lane stands Bosahan woods. The woods line the valley through which runs the unnamed stream whose source flows from the quarry scarred granite uplands to the north of the parish down this valley, through Ponjeravah until it is united with the Helford River and eventually the sea. Bosahan woods are another one of Cornwall’s hidden treasures, when I first arrived in the village in the early 1990’s the Bosahan woods was relatively unknown. With it gently bowing beeches, sycamores, hollies and hazels and its lively stream tumbling through great boulders at its base, it was a hidden sanctuary. In the spring the slopes beneath their bows would become alive with Bluebells. The bluebell is a member of the hyacinth family. It is said that if one cuts hyacinth bulb in half one sees a Hebrew letter corresponding to one of the names of god …except for the bluebell from which this holy letter is completely absent, for the bluebell belongs to Pan! In the spring the subtle sweet, sherbety scent of the bluebells amongst the trees can indeed be quite intoxicating.

Down a narrow gap between two houses down comfort lane on the edge of the village lays Comfort well. For many folks, when one thinks of a well, one thinks of a deep hole in the ground in to which one lowers ones bucket on a rope. There are some wells like this in Cornwall, but many of the wells are enclosed surface springs such as this one. The blurring of the line between what lays above and below the ground seems to be something inherent in both the Cornish landscape and the Cornish psyche. There is no evidence that this well was specifically recognised as a holy well with any kind of dedication attached but it was once one of the sources of domestic water for the village. The water courses beneath the land and the ways in which they flow are still an unseen mystery to the worlds of science and engineering; their mysteries are known only to the dowsers and the spirits of the wells. Many of the mine workings disrupted the unseen flow of the subterranean water courses and consequently many of the old springs and wells ceased to flow, but this well still runs pure and clear to this day.

At the end of comfort lane stands Bosahan woods. The woods line the valley through which runs the unnamed stream whose source flows from the quarry scarred granite uplands to the north of the parish down this valley, through Ponjeravah until it is united with the Helford River and eventually the sea. Bosahan woods are another one of Cornwall’s hidden treasures, when I first arrived in the village in the early 1990’s the Bosahan woods was relatively unknown. With it gently bowing beeches, sycamores, hollies and hazels and its lively stream tumbling through great boulders at its base, it was a hidden sanctuary. In the spring the slopes beneath their bows would become alive with Bluebells. The bluebell is a member of the hyacinth family. It is said that if one cuts hyacinth bulb in half one sees a Hebrew letter corresponding to one of the names of god …except for the bluebell from which this holy letter is completely absent, for the bluebell belongs to Pan! In the spring the subtle sweet, sherbety scent of the bluebells amongst the trees can indeed be quite intoxicating.

As with many woods in Cornwall, its idyllic nature masks an industrial past. At the head of the wood stands the old mine stack of Wheal Vivian. Through the C19 right up until the 1860’s and the crash of the Cornish mining industry this was a major producer of tin and copper. The Valley below would have been alive with the sound of stamps, machinery, carts and the coming and going of the workers. In an attempt to revive its fortunes after the collapse of mining the parish decided to turn its hand to granite quarrying, this industry too took a tumble in the same manner as its predecessor the mining industry …such is the inevitable nature of capitalism. By the 1950’s the golden moment of granite quarrying was mostly over in Cornwall. Bosahan quarry at the other end of the woods however continued working until 1993.

Opposite the great cyclopean granite edifice that once housed the wheel that drove the stamps to process the ore from the mine is a ruin of an old gate through which the lower track through the woods passes. It is known locally as the ‘funeral gate’ and many are reluctant to go there after dark. It is said that the old ‘coffin ways’ radiating from the parish church to the outlying farms were the first rights of way. Along them the coffin bearing the departed would be carried, often over quite some distance …and some say that the spirits of the departed still pass in their nocturnal perambulations. This gate could quite possibly be marking one such way. The style along the upper path in the wood is also said to be haunted. No one seems to now know the tale, though I have confidently been told on several occasions that the tale is in “All the ghost books”. If it is, I have never managed to find it. I have heard this recollection on a number of occasions regarding otherworldly tales. I strongly suspect that this banishing of the story to the confines of a ‘mythical’ tome is a way in which our fickle imaginations deals with the dichotomy that on one hand we don’t want to hang on to the tale and on the other we can’t bear to let it go.

The world of mining was a shadowy liminal world, fraught with danger but rich in opportunity. Not surprisingly it also provides a rich seam of folkloric beliefs. The C19 folklorists recorded an extant belief in the “Bucca’s” or the nameless numinous spirits of the mine who could cause disaster, or if the appropriate taboos and offerings were observed could also lead one to great wealth. I know of a surveyor of mines who whilst exploring one of the more recent levels of south Crofty mine in mid Cornwall (one of the last to close in the 1980’s) in recent years, observed and photographed a cairn of stones which was reputedly constructed from stones left by the miners as offerings to the Bucca’s, right up until its closing days. In 2016 the manager of nearby Trenoweth quarry (which is still in operation producing hand-worked monumental masonry to this very day!) showed me a manual which was presented to all granite workers in the area on the completion of their apprenticeship, up until the 1950’s. Amidst the technical data is also instructions on the use of a found stone bearing a cross formed of feldspar or quartz as a talisman – “he who finds the white cross is lucky from that hour – and many things.” The manager in question sported a fine example himself upon his works desk.

An old triad from the C19 describes the sight of an “old scat Bal” (an old ruined mine engine house) as one of the great sorrows of Cornwall. In the old industrial landscapes which have been reclaimed by the verdant claws of nature, one is left with a mixture of emotions; there is a scent of ghosts, a sense of melancholy and a hint of hidden tales as the revenants of its past peaks unbidden through the soil; but there is also a sense of a strange and almost surreal beauty pervading the air. Medieval field boundaries peak through the soil telling of another land history before the Mine arrived. Between the times of the mine and the quarry the woods seem to have become a beech plantation, which in 1945 was clear felled. The present wood is self-set semi-natural woodland rising up from the scrubland it left behind. In recent years new paths have been put in through the length of the wood. Such ‘improvements’ leaves one with conflicting emotions. It is a good thing that access is opened up for all to appreciate and enjoy the place, but ironically this process begins to transform the landscape in to something quite different to that which it was. As with the old tales …once faery treasure is exposed to daylight it becomes but autumn leaves. But to go in to the woods in the twilight one can feel the spirits of the woods are still very much in evidence. Let us hope that their powers of protection are still strong enough to hold fast the land.

One emerges from the woods past an old stone style where once fragments of discarded polished granite from the quarry were scattered. Above is an old spoil heap from where I once saw “The Beast”, the great black cat, slinking like a strip of liquid shadow along the hedge of the field below. Once whilst passing this style in the twilight, I inadvertently crossed a badger path. Its owner, a fearsome bull badger, appeared from the hazel bank above me hissing and growling. Something primeval inside sprung in to motion. I turned and growled back at him. Afterwards I was informed that this was probably the worst thing to do as badgers notoriously never back down. Fortunately for me, that evening he did. I am very fond of badgers, but sadly the sentiment does not seem to be reciprocated. Once one night, whilst cycling up the road at the entrance to the quarry a badger broke from the hedge and started to give chase. For their apparently stumpy and lugubrious form they are alarmingly fast runners! It was as much as I could do to keep ahead of him and it was only when I broached the top of the hill that I could gather enough speed to completely loose him. Once after taking the dogs for a night-time walk in the woods I had a visitation from a police officer the following morning, which appeared banging on the door of my caravan at a nearby farm where I was living at the time. He informed me that I had been sighted entering the woods with a big stick and some dogs and I was suspected of badger-baiting, at which I collapsed in laughter. He stood there for a moment looking mildly self-conscious and awkward and then blurted out – “You can’t just stand there laughing; you’ve got to say something for me to put in my report!” I told him that I was a vegetarian, I loved badgers and nothing could be further from my mind than baiting them. He looked at me apologetically and thanked me for my statement. At that moment his radio crackled in to life with a call back to the station. He looked both crestfallen and resentful for a moment, then after muttering about not wanting to go back to the station he looked up at my shabby old caravan and sighing said “I could live a life like this.” It’s not often that one is woken up by being accused of badger-baiting by a copper in the midst of an existential crisis. I politely informed him that I had to go to work and he left.

In spite of being one of our largest and most ubiquitous native mammals who has been with us since pre-history, folklore regarding them is remarkably thin on the ground. There is however a wonderful native America legend that tells of the origins of humanity. It says that we began our lives deep underground. Tired of the perpetual darkness we petitioned the gods to lead us to a new world of our own. We travelled onwards and upwards until we eventually reached a crack in the ground through which the daylight shone down upon us, but it was too narrow to get through. The badger and the deer took pity on us and with the deer’s antlers and the badger’s great claws; they chipped away until the hole was big enough for us to pass in to our new home in the upper-world. I could not help but think of the badger excavations in the fogou in the glebe woods.

Just over the road from the entrance to the quarry lay the old manor of Trewardreva. The settlement goes back at least a thousand years, once belonging to the Saxon church, it was seized by the Normans and thus it began its manorial journey through history, reaching its peak in the C18. Owned by a sea captain who disinherited his son, it fell in to hands of his son-in-law, a Falmouth barrister by the name of Charles Scott (who built the nearby Scott’s quay) who was known for his extravagant ways. Upon his death he left great debts. The family estate was consequently sold off. The house steadily declined until it was bought by the Foxes (whose butler apparently went by the name of badger!) in in the 1930’s. The foxes were a Quaker clan who were well established in the nearby maritime town of Falmouth and well known for their shipping interests and philanthropic works.

In a field behind the house there stands a curious stone. It is a smooth weathered granite boulder which was once pointed out to me as being called the “Elephant stone”, presumably due to its vast bulk and smooth grey undulating surface. It is a curious anomaly, standing out from the surrounding jagged rocks looking for the entire world as if it had been worn down by glaciation, but of course there were no such ice masses down here. There were three other such stones recorded by Charles Henderson in his monumental history of the parish in the 1920’s; the “Chair stone” at Trengove, what is known as the “Omega stone” near maen Toll (of which he erroneously reports as being destroyed) and the famous Tolmen stone …but that is another story! Once the parish was strewn with both free standing “Moor stone” and granite outcrops. This gentle pastoral landscape must have once looked not unlike that of Zennor or the wilder parts of Bodmin Moor. Over the last few centuries nearly all the stone was cleared and quarried on an industrial scale, doubtlessly along with numerous megaliths and other such strange rocks. Luckily some have still survived, and here is one such stone, standing like one of the great pre-diluvian chthonic spirits who formed the land in fathomless ages past, anachronistically frozen mid stride in one of our pleasant green fields.

On the track that runs behind the house stands the most striking horse trough I have ever seen! A gush of spring water flows in to a great carved granite bowl before cascading away in to a leat below. Directly opposite on the outside of the barn on the western end of the house a face peers out over the top of the slope of a corrugated roof which buts on to the wall. The wall is probably Elizabethan and the head is known to the family as the “Devils head” and is said to “keep the devil away from the house”. The use of apotropaic ‘primitive’ heads on Elizabethan houses is not unknown, but it is always such a joy to find them, their fixed brooding gaze telling a tale of other worlds passing unseen in our familiar shadows.

The world of mining was a shadowy liminal world, fraught with danger but rich in opportunity. Not surprisingly it also provides a rich seam of folkloric beliefs. The C19 folklorists recorded an extant belief in the “Bucca’s” or the nameless numinous spirits of the mine who could cause disaster, or if the appropriate taboos and offerings were observed could also lead one to great wealth. I know of a surveyor of mines who whilst exploring one of the more recent levels of south Crofty mine in mid Cornwall (one of the last to close in the 1980’s) in recent years, observed and photographed a cairn of stones which was reputedly constructed from stones left by the miners as offerings to the Bucca’s, right up until its closing days. In 2016 the manager of nearby Trenoweth quarry (which is still in operation producing hand-worked monumental masonry to this very day!) showed me a manual which was presented to all granite workers in the area on the completion of their apprenticeship, up until the 1950’s. Amidst the technical data is also instructions on the use of a found stone bearing a cross formed of feldspar or quartz as a talisman – “he who finds the white cross is lucky from that hour – and many things.” The manager in question sported a fine example himself upon his works desk.

An old triad from the C19 describes the sight of an “old scat Bal” (an old ruined mine engine house) as one of the great sorrows of Cornwall. In the old industrial landscapes which have been reclaimed by the verdant claws of nature, one is left with a mixture of emotions; there is a scent of ghosts, a sense of melancholy and a hint of hidden tales as the revenants of its past peaks unbidden through the soil; but there is also a sense of a strange and almost surreal beauty pervading the air. Medieval field boundaries peak through the soil telling of another land history before the Mine arrived. Between the times of the mine and the quarry the woods seem to have become a beech plantation, which in 1945 was clear felled. The present wood is self-set semi-natural woodland rising up from the scrubland it left behind. In recent years new paths have been put in through the length of the wood. Such ‘improvements’ leaves one with conflicting emotions. It is a good thing that access is opened up for all to appreciate and enjoy the place, but ironically this process begins to transform the landscape in to something quite different to that which it was. As with the old tales …once faery treasure is exposed to daylight it becomes but autumn leaves. But to go in to the woods in the twilight one can feel the spirits of the woods are still very much in evidence. Let us hope that their powers of protection are still strong enough to hold fast the land.

One emerges from the woods past an old stone style where once fragments of discarded polished granite from the quarry were scattered. Above is an old spoil heap from where I once saw “The Beast”, the great black cat, slinking like a strip of liquid shadow along the hedge of the field below. Once whilst passing this style in the twilight, I inadvertently crossed a badger path. Its owner, a fearsome bull badger, appeared from the hazel bank above me hissing and growling. Something primeval inside sprung in to motion. I turned and growled back at him. Afterwards I was informed that this was probably the worst thing to do as badgers notoriously never back down. Fortunately for me, that evening he did. I am very fond of badgers, but sadly the sentiment does not seem to be reciprocated. Once one night, whilst cycling up the road at the entrance to the quarry a badger broke from the hedge and started to give chase. For their apparently stumpy and lugubrious form they are alarmingly fast runners! It was as much as I could do to keep ahead of him and it was only when I broached the top of the hill that I could gather enough speed to completely loose him. Once after taking the dogs for a night-time walk in the woods I had a visitation from a police officer the following morning, which appeared banging on the door of my caravan at a nearby farm where I was living at the time. He informed me that I had been sighted entering the woods with a big stick and some dogs and I was suspected of badger-baiting, at which I collapsed in laughter. He stood there for a moment looking mildly self-conscious and awkward and then blurted out – “You can’t just stand there laughing; you’ve got to say something for me to put in my report!” I told him that I was a vegetarian, I loved badgers and nothing could be further from my mind than baiting them. He looked at me apologetically and thanked me for my statement. At that moment his radio crackled in to life with a call back to the station. He looked both crestfallen and resentful for a moment, then after muttering about not wanting to go back to the station he looked up at my shabby old caravan and sighing said “I could live a life like this.” It’s not often that one is woken up by being accused of badger-baiting by a copper in the midst of an existential crisis. I politely informed him that I had to go to work and he left.

In spite of being one of our largest and most ubiquitous native mammals who has been with us since pre-history, folklore regarding them is remarkably thin on the ground. There is however a wonderful native America legend that tells of the origins of humanity. It says that we began our lives deep underground. Tired of the perpetual darkness we petitioned the gods to lead us to a new world of our own. We travelled onwards and upwards until we eventually reached a crack in the ground through which the daylight shone down upon us, but it was too narrow to get through. The badger and the deer took pity on us and with the deer’s antlers and the badger’s great claws; they chipped away until the hole was big enough for us to pass in to our new home in the upper-world. I could not help but think of the badger excavations in the fogou in the glebe woods.

Just over the road from the entrance to the quarry lay the old manor of Trewardreva. The settlement goes back at least a thousand years, once belonging to the Saxon church, it was seized by the Normans and thus it began its manorial journey through history, reaching its peak in the C18. Owned by a sea captain who disinherited his son, it fell in to hands of his son-in-law, a Falmouth barrister by the name of Charles Scott (who built the nearby Scott’s quay) who was known for his extravagant ways. Upon his death he left great debts. The family estate was consequently sold off. The house steadily declined until it was bought by the Foxes (whose butler apparently went by the name of badger!) in in the 1930’s. The foxes were a Quaker clan who were well established in the nearby maritime town of Falmouth and well known for their shipping interests and philanthropic works.

In a field behind the house there stands a curious stone. It is a smooth weathered granite boulder which was once pointed out to me as being called the “Elephant stone”, presumably due to its vast bulk and smooth grey undulating surface. It is a curious anomaly, standing out from the surrounding jagged rocks looking for the entire world as if it had been worn down by glaciation, but of course there were no such ice masses down here. There were three other such stones recorded by Charles Henderson in his monumental history of the parish in the 1920’s; the “Chair stone” at Trengove, what is known as the “Omega stone” near maen Toll (of which he erroneously reports as being destroyed) and the famous Tolmen stone …but that is another story! Once the parish was strewn with both free standing “Moor stone” and granite outcrops. This gentle pastoral landscape must have once looked not unlike that of Zennor or the wilder parts of Bodmin Moor. Over the last few centuries nearly all the stone was cleared and quarried on an industrial scale, doubtlessly along with numerous megaliths and other such strange rocks. Luckily some have still survived, and here is one such stone, standing like one of the great pre-diluvian chthonic spirits who formed the land in fathomless ages past, anachronistically frozen mid stride in one of our pleasant green fields.

On the track that runs behind the house stands the most striking horse trough I have ever seen! A gush of spring water flows in to a great carved granite bowl before cascading away in to a leat below. Directly opposite on the outside of the barn on the western end of the house a face peers out over the top of the slope of a corrugated roof which buts on to the wall. The wall is probably Elizabethan and the head is known to the family as the “Devils head” and is said to “keep the devil away from the house”. The use of apotropaic ‘primitive’ heads on Elizabethan houses is not unknown, but it is always such a joy to find them, their fixed brooding gaze telling a tale of other worlds passing unseen in our familiar shadows.

Following the track along to the road one comes across another fascinating and enigmatic feature; it is a walled of corner of a field known locally as “The devils corner”. These small rectangular enclosures with no apparent entrance are not uncommon in Cornwall. They are hard to date and precious little about them is known. In a tradition collected in nearby Halvasso, it was suggested that unlike the “Devils head” which repels him, the “Devils corners” were there to contain the devil. This seems to be cognate with the phenomena of the “Devils acre” common in Scotland and the north, which perhaps in harking back to an older animistic age the farmers would leave a small area of set-aside for the old spirits of the land. The old gods never really die, just change their form. The road the devils corner buts on to also bears its own tales. Along the this narrow lane from Chegwidden and Brill (which is said to derive its name from the old Cornish for “The hill of hunting”) it is also said that the ghost of Charles Scott remains to this day, haunting the lane between Brill and Tregwidden upon his horse leading his phantom hounds. The tale of the spectral “Wild hunt” rears its head once again!

Across the road is the jewel in the crown of the antiquities of the parish, the Piskies hall fogou. The Fogou is of an enigmatic class of underground prehistoric passage chambers of which a number are to be found in Cornwall. Built in the age of the Celts they were the last of the great megalithic structures to be made.

Across the road is the jewel in the crown of the antiquities of the parish, the Piskies hall fogou. The Fogou is of an enigmatic class of underground prehistoric passage chambers of which a number are to be found in Cornwall. Built in the age of the Celts they were the last of the great megalithic structures to be made.

Their purpose unknown, we are led by default to suspecting a ceremonial purpose to their being. They are indeed strange numinous spaces, filled with an almost unnatural stillness. Local tales tell of Piskies being active down here, in fact the old name for the field in which it stands was “Piskies field”. At midwinter the low sunset shines directly upon the entrance filling the dark chamber with light, thus an ancient mystery in enacted. It is not far from the road on private land in a field usually populated by less-than-friendly cattle and is notoriously difficult to find.

To the north one looks across the great brooding sweep of the valley where once upon a rocky crag the great Tolmen stone stood. James Fox in the 2001 “Book of Constantine” intriguingly states that another underground chamber, thought to be of the same period has been found in a field nearer the main house!

©Steve Patterson

To the north one looks across the great brooding sweep of the valley where once upon a rocky crag the great Tolmen stone stood. James Fox in the 2001 “Book of Constantine” intriguingly states that another underground chamber, thought to be of the same period has been found in a field nearer the main house!

©Steve Patterson